Manchester Central: How City helped United to survive

By Gary James, Fri 21 October 2011 11:22

Eighty years ago, United were struggling, dying in fact, and City were dominant. Yet City did more than you’d expect to help United survive against a third club that threatened the Reds’ existence.

Manchester football historian Gary James explains how football history in the north-west could have been very different had Central been given a League chance. This is an adapted version of a story first revealed in Gary’s excellent “Manchester A Football History.”

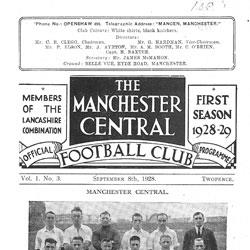

In recent years much has been made of the growth of FC United of Manchester and their impact on support, community work and attitudes in Manchester. However, the United offshoot were not the first Mancunian side created following dissatisfaction among supporters. In fact FC United arrived 80 years after a bigger offshoot had seriously challenged the livelihood of Manchester’s two major sides. The difference being that in the Twenties it was Manchester City’s move to Maine Road that prompted the creation of a new forward-looking club – Manchester Central FC, who joined the semi-professional Lancashire Combination in 1928-29.

One of the main figures behind Central was former City director John Ayrton, who that felt that Maine Road, in the south of Manchester, was too far from City’s old base in the east: “Ever since the City club left the Hyde Road district, I have thought of having a club on this side of Manchester. Our whole object is to develop local talent, and gradually to build up the club so that one day it may take its place in the Third Division of the Football League. Manchester has the biggest sporting community in the provinces. Surely then we have every reason to hope that there is plenty of room for our club.”

Many well known figures in Manchester football were involved in the creation of Central, including the great Billy Meredith, plus Charlie Pringle and Charlie Roberts, former captains of City and United respectively. As with FC United, the side attracted significantly better players than many of their Combination rivals – who included Morecambe, Chorley and Darwen – simply because of who they were. Central was chosen as a name so that the club could use the initials MCFC, which were spelt out on the ironwork above the main entrance of their 40,000-capacity Belle Vue ground on Hyde Road, half a mile from City’s old stadium.

After a couple of failed attempts, Central were on the verge of League football when Wigan Borough withdrew from Division Three (North) during October 1931. Central, now based in the Cheshire League, immediately offered to take over their fixtures. The existing Division Three sides supported Central’s application, including, significantly, Stockport County, who saw Central’s acceptance as being a positive development for local football.

In the Daily Dispatch, journalist “Adjutant” commented: “Manchester Central potentially are not merely a Second Division, but a First Division club of the future. There should be room in Manchester for three League clubs.” Second Division United and First Division City did not share the enthusiasm. Working together they complained to the League and, as they were classed as full members of the League while Division Three’s clubs had fewer rights, the League rejected Central.

The local press was appalled, as were many City and United supporters. So why did the two clubs object? At first glance it would seem that Central’s aim to be “the new MCFC” simply upset City. However, the truth is that Central were actually more of a threat to United, who were struggling on and off the pitch. Crowds were small – United’s nearest home gate to Central’s bid was 6,694 (against Notts County) and that was almost double United’s crowd for the opening game of the season at Old Trafford (3,507). Central attracted several crowds higher than this despite being non-League.

Respected journalist Ivan Sharpe of the Sunday Chronicle argued that Central should have been admitted because United were failing: “A third club in Manchester would not damage the City at all seriously. It would build up football interest. I don’t like the way Manchester is slipping back in football. Where are those 30,000 football followers who used to assemble at Old Trafford? The odd 25,000 are missing. It is time something was done about it.”

Central were hugely disappointed and chairman George Hardman said: “We think there ought to be League football in the Belle Vue area, where there are 440,000 people within two miles, and a million people within four miles. This is surely enough for two League clubs in a place like Manchester. There seems to be a sad lack of enterprise so far as League football is concerned.”

It seems Hardman deliberately ignored United when he talked of “two” clubs as he knew it was the threat to United that was the deciding factor. Ivan Sharpe: “In view of Manchester United’s sorry position I certainly think Manchester Central should have been admitted.” “Nomad”, writing in the Evening Chronicle, held a similar view: “Keen disappointment is expressed that Manchester is not to have a third Football League club, especially as there is a splendid ground available at Belle Vue, and that Manchester United are so signally failing to keep Manchester on the football map.”

Within a year Central folded, feeling the close relationship of City and United would continue to severely restrict their progress. At City the 1930s proved to be a golden era with record crowds and significant success, while United struggled. Post-1945 it all changed, of course, but had Central been accepted into the League during 1931 then football in Manchester today might have been very different.

For more information about Gary’s books have a look at: http://www.facebook.com/GaryJames4

Manchester - A Football History is the definitive record of the development of football in the Manchester region and has significant content of interest to City fans.

To buy “Manchester A Football History” click here.

Archives