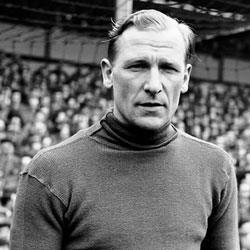

A tribute to a true City legend who has sadly passed away aged 89

A tribute to a true City legend who has sadly passed away aged 89

Bert Trautmann was not only one of City’s greatest ‘keepers, he is also one of football’s most important figures. He is one of the Football League’s 100 greatest legends; one of City’s most popular players - he received more votes than any other player in the City Hall of Fame when I created the awards in 2004; and he is one of sport’s greatest ambassadors. He is also the main reason why my father became a Blue, and therefore is the reason I’m a City fan. Thousands of others have him to thank for their City roots.

Trautmann’s upbringing and early life has to be considered in the context of the country he grew up in. Germany during the late twenties and thirties was at times a desperate place to be. The country was on its knees following the First World War and the early years of the depression. It was an environment in which the far right policies of Adolf Hitler flourished.

As a youngster Trautmann, already a keen sports enthusiast, became a member of the Hitler Youth. It wasn’t as a result of strong political beliefs; he was simply following the route expected. During the war he joined the Luftwaffe and served in Poland and Russia. As a paratrooper he was captured by the Russians and by the French Resistance, escaping on both occasions, and won five medals for bravery including the Iron Cross (first class).

Trautmann saw the full horrors of war. It was a nightmare existence, although Trautmann has always been quick to point out it was no worse than the situation millions of others were in: “There was tragedy and there was humour, as there was on every battle front.”

In 1945 he was captured by the Americans but somehow managed to walk free. Then the British caught him and eventually he was taken to a camp in Ashton-In-Makerfield. It was at this camp that he began to play in goal for the first time during football matches.

Trautmann was officially released from captivity in February 1948 but elected to stay in Britain as he saw no immediate prospects in Germany. Agricultural work and bomb disposal activities followed, and whenever possible he was playing football for St. Helen’s Town.

As the 1949 season commenced several League clubs were showing interest in him. By that time City had hastened their search for a replacement to Frank Swift and the Club’s management were ready to take a gamble on Trautmann. It is often overlooked that City’s desperation to find a replacement for Swift caused the side to controversially select the former Prisoner of war.

City signed Trautmann in November 1949 but the move was not popular. For at least a month prior to the transfer newspapers were publishing letters from fans threatening to boycott the club. City had a large Jewish support and many believed the arrival of a former German paratrooper was one step too far. The national media soon caught on to the story and considerable negative publicity was generated. The Club could have pulled out at any point, however Chairman Bob Smith answered critics by saying: “People can boycott or not as they like. I am very glad we have signed Trautmann. From what I have heard of him he is not a good goalkeeper, he is a superb goalkeeper. We had to get him in quickly or other teams would have taken him from under our noses.” It was a very brave decision.

The players, including Captain Eric Westwood – a Normandy veteran, soon made Trautmann feel welcome. That all helped and then came Trautmann’s debut on 19th November 1949 against Bolton. The Blues lost 3-0 but the ‘keeper had impressed. Trautmann remembers this period as one of transition: “It was the first time I actually saw people protesting against me. But within a month, a lot of those same people who’d been against me were having a go at anyone having a go at me! It changed very quickly. When I signed for City the ‘papers were full of discriminating headlines along the lines of ‘If City sign a Nazi, what next?’. And then people realised I’d been digging unexploded bombs in their country. They started to see me as a person with a mother and father. It was all about the human touch.”

Trautmann quickly established himself as a worthy successor to Frank Swift, and the former England captain went to great lengths to stress the quality of the German. City fans adopted Trautmann as one of their own and the ‘keeper became more important to the Blues after every game. One game in particular, away at Fulham in January 1950, saw Trautmann in outstanding form. This was a landmark game for the ‘keeper as at the start of the match his appearance had not been welcome. Trautmann: “I had been getting a good press in the north-west by this time, but Jack Friar, who was to become my father-in-law, pointed out that my first game in London would really test me because of the papers and publicity down there. He said I wasn’t just playing against Fulham, I was playing against London. I needed to make a good impression to get the national press on my side, and he told me he expected we could lose 7-0 or 8-0!”

As the players entered the Craven Cottage pitch shouts of ‘Kraut’ and ‘Nazi’ rang out. Trautmann received tremendous abuse and clearly a lesser player would have buckled under the pressure, but the ‘keeper seemed to see the venom as a challenge, and he started to appear more confident and more determined than he had in any earlier City match. In the end the Blues lost 1-0, but the score would have been much worse had it not been for Trautmann: “I was at the Thames End of the ground and was the last player to come off. Both teams stood at the dressing room entrance and applauded. A very emotional moment. In London, at that time, that was a testimony. I was lucky in later years to win the FA Cup; win the player of the year, and play for the Football League. But Fulham was my greatest moment.”

The attention the player was now receiving was all positive, and the German media were beginning to show interest. This led to attention from German League sides, including Schalke ’04 who made an offer of £1,000 for the player. City rejected the bid, but for a while Trautmann became keen to return to Germany.

In 1955 Trautmann became the first German to play in a FA Cup final: “Today, I don’t think the occasion means that much anymore in terms of the community spirit and everyone singing ‘Abide With Me’ and so on. When I went there I enjoyed the whole thing – the build up… the media attention… everything. I have never known nerves like I had that day. Even when we went back a year later, they were still bad.”

At Wembley in ’56 Trautmann helped City defeat Birmingham City. It was a memorable game but for many the significant aspect of the day concerns Trautmann. Trautmann: “It was only years later I could piece together what happened that day. I have watched film of the match and you can see me coming out to intercept the ball. I was in the air and neither me nor Murphy, the Birmingham player, could stop. He tried to get over me, lifted his leg but caught me in the neck with his right leg. It was accidental. After that I was gone. Everything was grey until the final minute. I made a couple of saves but don’t remember anything until our centre-half, Dave Ewing, collided into me. The pain was intense and I really didn’t know what I had done. I was only aware of this pain – like an extreme toothache in my neck.”

“On Sunday morning I was taken to hospital in London where they took X-rays and told me it was nothing. But I could not move my head. If I wanted to turn I had to move my whole body. I knew something was wrong.”

Incredibly Trautmann played his part in City’s homecoming and he made an impromptu speech at the Town Hall while the crowd chanted his name. Trautmann: “I must have looked like death. We had the homecoming in a packed Albert Square and I had to speak. At the reception I remember Frank Swift slapping me with his enormous hands – it felt like I had been split right down the middle with an axe!”

Unhappy with his medical treatment, Trautmann arranged to see an expert the Tuesday after the final. That’s when the true extent of the injury became apparent. The Doctor told Trautmann he had broken his neck.

A few weeks after the final further tragedy struck when Trautmann’s son was killed in a road accident. Life was tough, immediately after Wembley, but Trautmann tried to be positive: “There was nothing I could do but lie there and do a lot of thinking. And never did I think that I would not play football again.”

Then in December – only seven months after the injury – he returned to League action. His return came on 15th December 1956 – the first City League match filmed by the BBC at Maine Road. Trautmann: “It was very difficult coming back. I came back too quickly really. I would stand there with the forwards coming at me, saying ‘Come on, have a go. Let me show you I’m still good enough’. But it never happened like that. I reckoned I was finished. I told McDowall so, but he told me I was wrong. I told him I had cost City at least six points but he said ‘think of the number of points you’ve saved us over the years’. I think it took me about 18 months before I was fit enough but, even today, my neck is still painful and restricted, especially in cold weather.”

Trautmann continued to play for City until 1964 when he was awarded a testimonial. By that time he had eclipsed Eric Brook’s first team appearance record for the Blues and inevitably fans were desperate to give him a great testimonial. The official crowd was approximately 48,000, however the actual attendance was at least 60,000 as Maine Road was packed to the rafters with thousands locked outside.

During the latter part of his time at City, Trautmann was viewed by the English authorities as the greatest goalkeeper playing in England, and in October 1960 he was chosen to captain the Football League’s representative side for a match with the Irish League. This was a major honour at the time and compensated, to some degree, for the fact that he had not been picked to play for his national side. The reason he never appeared has been debated many times over the years. The most likely reason is that the German authorities had simply chosen not to pick him because he was playing outside of his home nation. Had he joined Schalke in the early fifties he would probably have been a regular for his national side.

Despite this, it’s fair to say Europe’s leading footballing figures recognised his greatness, especially in 1956 when he was awarded the Football Writers’ Player of the Year award. This is not only significant because Trautmann was the first overseas player to receive the award but also because it was awarded to him in the days leading up to the 1956 final. Therefore his heroics that day played no part in the decision.

After leaving the Blues spells at Stockport County and Wellington Town followed as player-manager, plus various spells working with the German FA. He had a significant role assisting Third World countries with the development of sport. Stints in Burma, Tanzania, Liberia, and Pakistan presented him with many obstacles but, as with his playing career, Trautmann was determined to succeed. These activities prove beyond doubt the importance of Trautmann to sport. As a player he had achieved so much. As a man he achieved more. Born in a country at a time when prejudice and bigotry was the norm, Trautmann’s experience in England helped him develop as a man. His role as a sporting ambassador helped to break down barriers, remove prejudice, and encourage people from all walks of life and backgrounds to work and play together. He was later awarded the OBE for his contribution to Anglo-German relations. Often sportsmen receive awards simply because of success on the pitch, Trautmann’s accolade is not solely for activities on the pitch (if it was he would have received it over forty years ago), it is for the example he has set throughout his adult life.

Trautmann is a true sporting legend and a great ambassador. He is also, arguably, the greatest European goalkeeper of all time.

During 2008 writer and actor Bill Cronshaw wrote and starred in “I’ll Be Bert” - a stage play focusing on how the ‘keeper had affected a young boy’s life.

Bert passed away aged 89 on July 19th, 2013 and is survived by his wife Marlies.